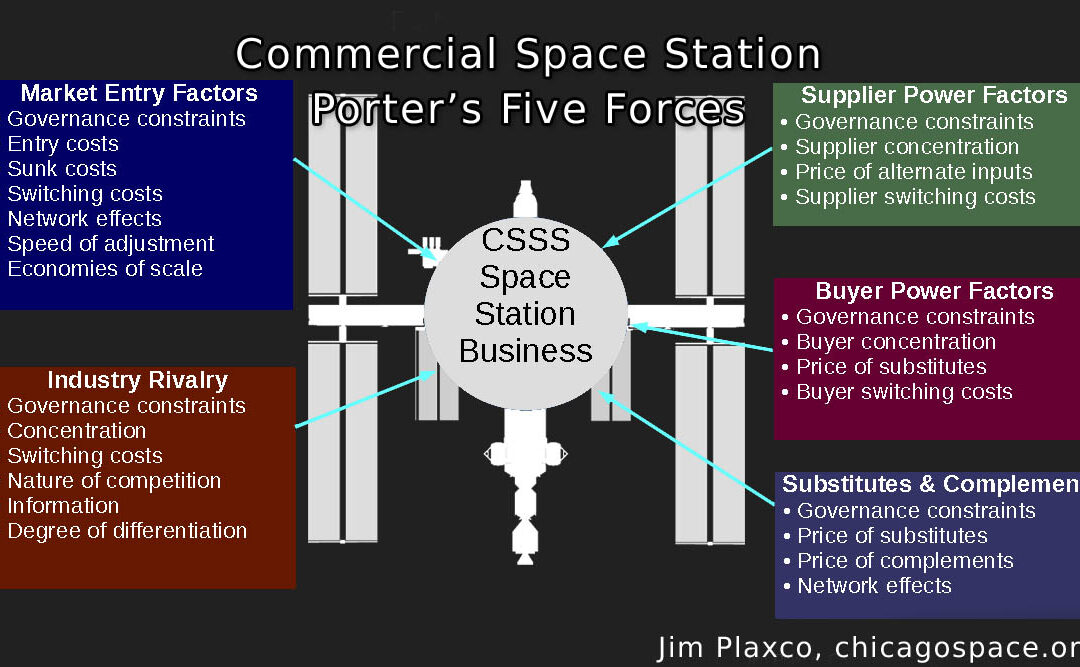

Figure 1. Porter”s Five Forces model applied to a commercial space station business.

This essay is an expansion on the Porter’s Five Forces section of the presentation Evaluating the Market for Commercial Space Stations originally presented at the 2023 International Space Development Conference.

An Introduction to Porter’s Five Forces Model

Porter’s Five Forces Model is a framework for characterizing the business environment of a particular market or industry. It does this by analyzing the internal forces seen as impacting that market’s competitive environment. Michael Porter, who created the model, identified five categories of forces that impact a market or industry. The five forces are:

- Market Entry

- Industry Rivalry

- Supplier Power

- Buyer Power

- Substitutes and Complements

The Market Entry force looks at how easy or difficult it is for a new business to enter the industry or market in question.

The Industry Rivalry force characterizes the nature and degree of competition between the businesses that are operating in that industry or market. The more intense the degree of industry rivalry, the less pricing power a business will have, which equates to less profitability.

The Supplier Power force addresses the strength or bargaining power of those businesses from whom players in the industry or market must purchase the supplies they need in order to conduct their business.

On the other side of the equation, the Buyer Power force looks at the ability of the business’s customers to negotiate purchase prices and terms of purchase.

Lastly, the Substitutes and Complements force looks at the extent and nature of both substitute goods and complementary goods. Substitute goods are those goods that serve as alternative goods for the customer. These are the products your customer could buy instead of the product your industry sells. Complementary goods are other goods that your customer can buy which enhance the value of the goods you are selling. A classic example of complementary goods is that of hot dogs and hot dog buns where the price and availability of one impacts the demand for the other. Another example of a complementary good that is relevant to this discussion is the relationship between the price of gasoline and the use of automobiles.

Collectively, the combination of these five forces will impact a firm’s degree of competitive advantages in the market, the ability of a firm to manage its costs and set prices, and the overall profitability of firms in that industry.

In characterizing and understanding the market forces that impact the economic sector within which commercial space stations will operate, Porter’s Five Forces Model helps us to gauge the likelihood of success, or failure, for both new and existing space station enterprises.

Porter’s Five Forces: Market Entry

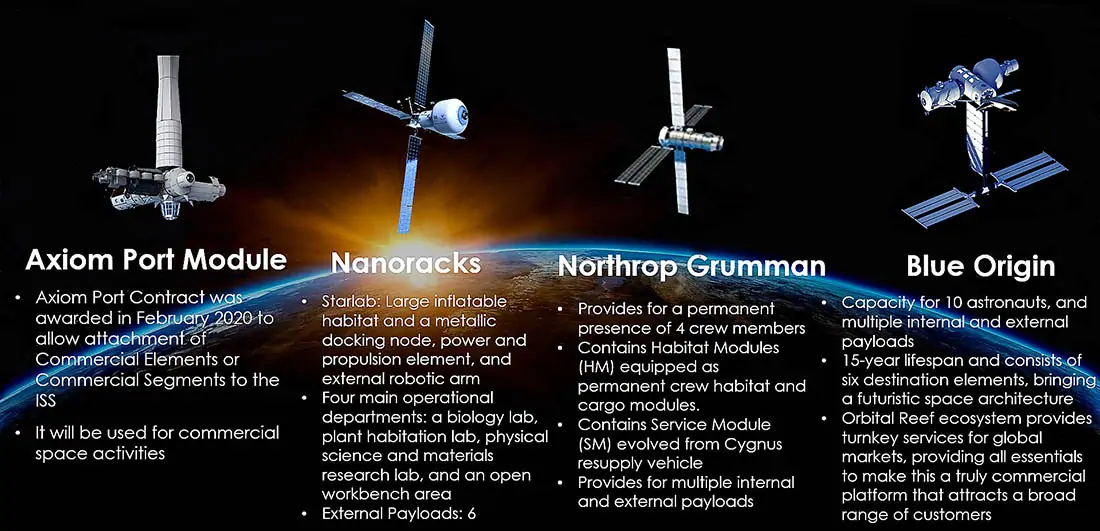

Figure 2. Space station projects that have Space Act Agreements with NASA. The NASA Commercial LEO Destinations program is an example of a government policy that is encouraging business entry into the space station market.

Market entry forces deal with those factors that determine how hard it is for a new business to enter a particular market. For the commercial space station market, the main market entry factors are the amount of capital required to finance the business; the amount of time needed to design, build, and launch a space station; the nature of economies of scale for the industry; the nature and complexity of the government’s regulatory policies for the industry; and the degree to which the industry’s existing customers are bound to existing space station businesses.

With respect to regulatory policy, the commercial space industry is heavily regulated by government agencies such as the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). There is also the regulatory challenge of dealing with trade restrictions associated with technology transfer. And because this is a new industry, the regulatory environment is a rapidly evolving one in comparison to that of well-established industries.

For a new entrant into the space station industry, a competitive barrier to entry would be the extent to which the existing customer base has long-term contracts with existing space station businesses as well as the extent to which existing launch providers have long-term contracts with those space stations.

This leads to the question of switching costs – how much in additional costs a customer incurs when switching from one space station provider to another. A computer industry example of non-financial switching costs is demonstrated with the now out of date phrase “Nobody gets fired for buying IBM” There was a time when IBM was the leading computer company and seen as being an industry leader and buying computers and associated services from them was seen as being the lowest risk option, even if it wasn’t the cheapest option.

At present, government policy with respect to the NASA Commercial LEO Destinations program is oriented to expedite the entry of commercial space stations into the market in order to serve as replacements for the International Space Station (ISS) which is to be retired in 2030.

Porter’s Five Forces: Industry Rivalry

Figure 3. In addition to space station projects receiving funding from NASA Space Act Agreements, other companies are entering the arena both as operators and as suppliers of modules.

The nature of an industry’s competitive rivalry is an indicator of how hard businesses in that industry must work to capture, retain, and protect market share as well as how profitable those businesses may be. For example, a market wherein one or two companies dominate will be very different with respect to pricing power than a market with many competing businesses with an equal division of market share.

In the case of the space station market, which should be viewed as a start-up industry, not only will a space station operator have to deal with competition from participants in the NASA Commercially Developed Free Flyer and NASA Commercial LEO Desitinations programs, but with government owned and operated space stations like China’s Tiangong and other commercial entrants.

In addition to the commercial space station projects that have Space Act Agreements with NASA, other companies that responded to the NASA Commercial LEO Destinations call include:

- DEHAS Limited

- Hamon Industries

- Maverick Space Systems Inc.

- Orbital Assembly Corporation

- Relativity Space Inc.

- Space Exploration Technologies Corporation

- Space Villages Inc.

- ThinkOrbital Inc.

It remains to be seen how many space station businesses will actually achieve an operational status, as opposed to being on-paper-only businesses.

Porter’s Five Forces: Supplier Power

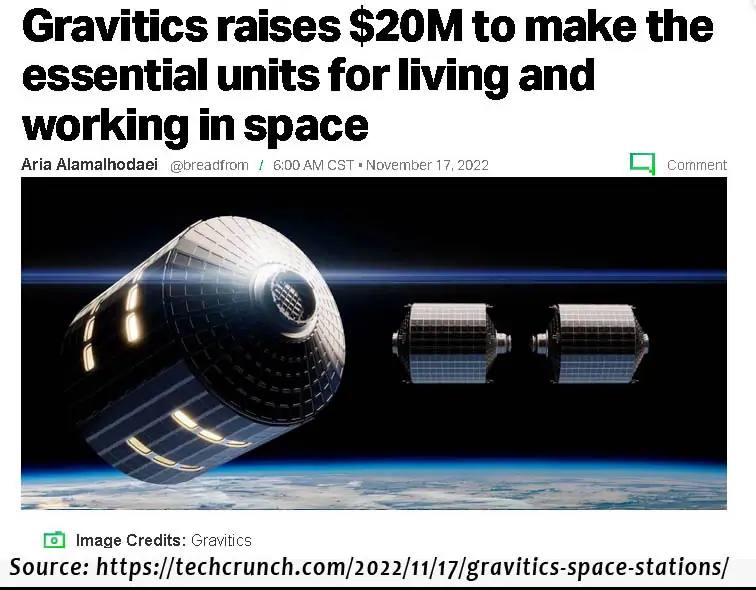

Figure 4. A McKinsey chart illustrating the possible range of demand for launch services in an attempt to identify whether or not there will be a supply surplus or shortage for launch services.

Supplier Power addresses the degree to which a business’s suppliers are able to dictate price and purchase terms. In the case of space stations, the primary supplier of concern will be that of the launch industry.

The extent to which launch providers can dictate price, launch frequency, launch scheduling, and payload packaging requirements will impact a space station’s cost structure and consequently the prices space station operators must charge for their services. Ideally, space stations will be dealing with a growing launch industry that has a high degree of industry rivalry and an ongoing greater supply of launch services than are currently demanded by the market. These factors will provide space station businesses with a greater degree of cost control and predictability for their business.

With respect to the launch industry, over the longer term the question of Supplier Power will be one of whether or not the demand for launch services is growing faster than the supply or whether the supply of launch services is growing faster than demand. The degree of supply uncertainty is illustrated in Figure 4 from McKinsey & Company which attempts to forecast the supply of launch services out to 2030. This degree of uncertainty represents an additional challenge to the purchasers of launch services. Never forget that for a business, the degree of uncertainty equates to a level of risk for that business.

Porter’s Five Forces: Buyer Power

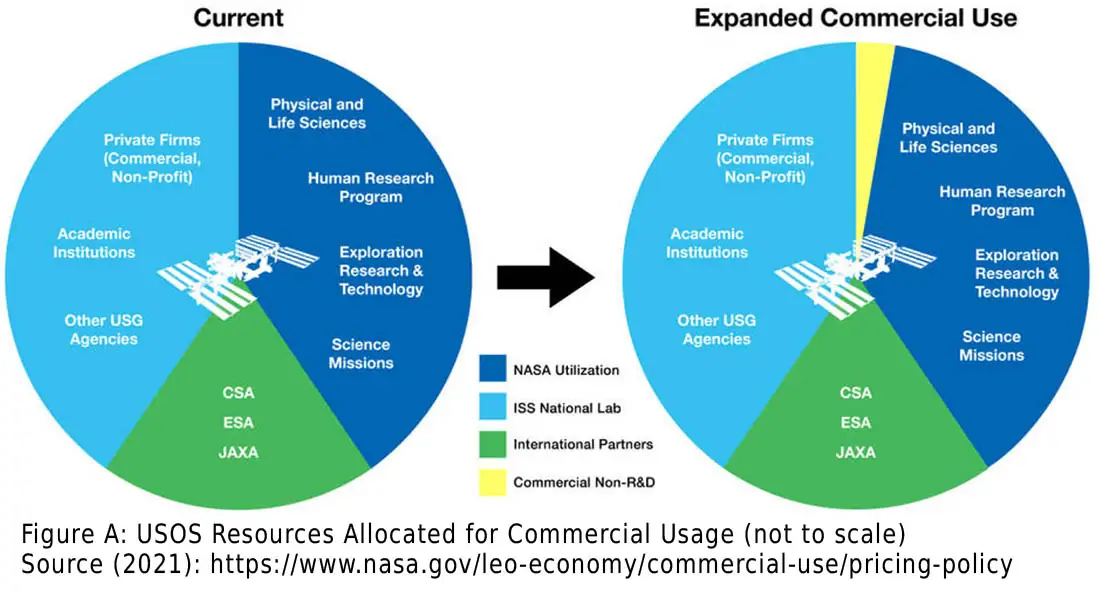

Figure 5. NASA graphic reflecting the allocation of ISS resources by customer type (government, institutional, commercial) and for NASA, by research type.

Buyer Power looks at the number of customers in a market and the customer’s sensitivity to price (elasticity of demand). Because the market for space station services has not yet been established, the information about buyers that is available is very speculative.

To date, the market for space station goods and services is effectively a monopsony – a market dominated by one single customer. For the space station market, that customer is the U.S. government.

On the positive side for a space station business, government agencies are minimally sensitive to the prices of the goods and services they purchase since these institutions are more policy oriented than value oriented. Academic institutions are more sensitive to price but not as price sensitive as are commercial operations for whom the creation of value determines whether or not that business stays in business or goes out of business.

Porter’s Five Forces: Substitutes and Complements

Figure 6. ISRO, India’s national space agency is considering entry into the space tourism market. Their plan can be seen as a substitute good for space station tourism services, thus negatively impacting space station revenues.

The last of Porter’s Five Forces deals with the issue of substitute goods and complementary goods. Substitutes would be products and/or services the consumer could purchase instead of those offered by a space station business. For example, tourist stays on a space station are seen as being a key source of revenue but what if a non-space station business begins offering orbital trips to space to a variety of orbital inclinations aboard a large launchable capsule designed specifically to host tourists for up to a week and then return to Earth? What would be the impact of such a space tourism service on a space station’s revenue stream and business model?

Another example of a substitute good is that of either orbital or sub-orbital flights for experiments needing shorter periods of access to a microgravity environment. Will a cost-benefit analysis result in a significant number of experimenters choosing a lower cost, non-space station alternative?

Though not a substitute, another consideration that could fall within the boundaries of product differentiation is the potential for lights-out operations space platforms that are dedicated solely to research and development experiments or in-space manufacturing projects that require no human involvement. Could such a facility offer platform services that are only marginally less flexible than those offered by fully manned space stations but at a small fraction of the price?

Less-well understood is the nature and value of complementary goods, which are those products, be they a good or a service, that serve to make your own product more attractive. It may be the case that satellite servicing, orbital refueling, and orbital debris removal services become seen as being complementary goods. However, the foundational complementary good will be launch services. It is the affordability of this good that will be the primary driver in the development of a LEO (Low Earth Orbit) economy.

Porter’s Five Forces Summary

Having performed a survey of Porter’s Five Forces of Market Entry, Industry Rivalry, Supplier Power, Buyer Power, and Substitutes and Complements, the key question is whether or not these forces combine to paint a favorable picture of the commercial space station market. Note that given the lack of operational history and historical market data, any appraisal of these five forces is highly subjective.

At this point in time, the Market Entry Force can be weighted as being somewhat positive. While high capital costs and long lead times serve to hinder market entry, this aspect of market entry should not be viewed as entirely negative because there are no established space station businesses. Lending weight to a positive assessment of this force is the decision by the U.S. government to rely on commercial space stations as a replacement for the International Space Station and the subsequent policy decisions to promote market entry via NASA Space Act Agreements,

Given that there are no operational commercial space stations, the Industry Rivalry Force can also be seen as a positive factor for new entrants. The first space stations to enter operational service should best be able to establish brand recognition and begin work on building customer loyalty. For additional critical insight on the concept of the first-mover advantage, see the Harvard Business Review article The Half-Truth of First-Mover Advantage.

Given the trends in commercial launch services, even with the degree of uncertainty associated with launch market forecasts, Supplier Power can be seen as a positive factor for the space station industry.

With respect to Buyer Power, this force is likely to be initially a negative for commercial sources of revenue but a positive for governmental sources of revenue. In the longer term, buyer power could change from negative to positive as the value of space station goods and services are proven to be worth their cost.

The nature of the Substitutes and Complements Forces component can be characterized as neutral given the lack of hard data for the market. While there is clearly growth potential in the market for the services space stations can provide, the rate of growth, the stability of that growth, and whether or not alternative Earth-based or orbital substitutes become available are largely unknown thus making the market for space station services highly speculative.

A Market Oriented Caveat

In discussing the nature of the market for commercial space stations, a crucial consideration is the total size of the market for all space station products and services. Is this market large enough to support multiple, competing commercial space stations – or even one? And how much of a market share hit will a commercial space station take if other government-owned space stations come online and begin to compete for the same customers?

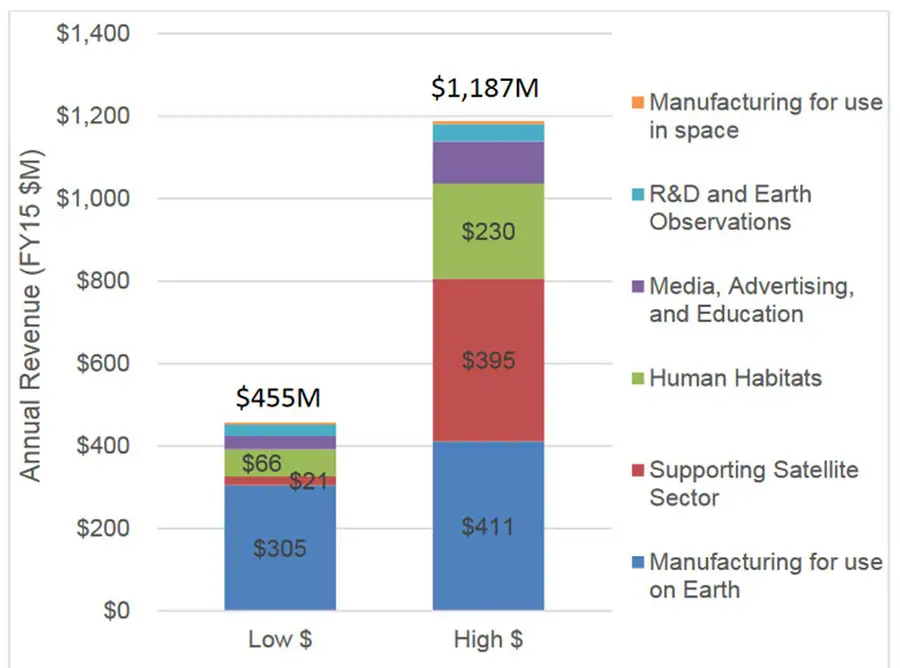

Figure 7. Distribution of Projected Annual Revenues for the (Commercial) Space Station, IDA Science & Technology Policy Institute Market Analysis of a Privately Owned and Operated Space Station, 2017. Available online at https://www.ida.org/-/media/feature/publications/m/ma/market-analysis-of-a-privately-owned-and-operated-space-station/p-8247.ashx

With respect to the size of the market for commercial space stations, in 2017 the IDA Science & Technology Policy Institute produced a report Market Analysis of a Privately Owned and Operated Space Station that characterized and quantified the market for commercial space station services.

The study provided two cost scenarios for space station operations: a low cost scenario and a high cost scenario. The study then identified two market size scenarios: a small market yielding a small revenue stream and a large market yielding a large revenue stream. In cross-referencing these scenarios, the study found that a commercial space station would only be profitable if it was a low cost space station with a large market producing a large revenue stream. While the study did show that there was a path to profitability, it assumed that a single space station received 100% of the market’s revenue. The introduction of a second or third space station would split this revenue stream, thus greatly increasing the risk that none would be profitable.

While our lack of experiential knowledge of the market for commercial space stations means that there is a relatively high level of risk for these business ventures, it is most certainly a risk worth accepting given the potential advances in the fields of pharmacology, biology, physiology, physics, combustion science, manufacturing, metallurgy, et al. For information about the benefits associated with the International Space Station, read the NASA publication International Space Station Benefts for Humanity 2022.

In this vein it is worth recalling President Kennedy’s statement about going to the Moon: “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”